In part 1 of this 3-part blog series, I explained why clean rooms are useful. A key pillar of my argument was that clean rooms help maintain anonymity.

To explain why this matters so much, let’s revisit some fundamentals on what anonymisation is and how it’s helpful.

What qualifies as “anonymous” data?

After a long period (10+ years) of relying on a few specific case law precedents from pre-GDPR, the UK data regulator, the ICO, issued very helpful guidance on anonymisation in March 2025. In it, they define anonymisation as follows:

“…the way in which you turn personal data into anonymous information, so that it then falls outside the scope of data protection law.”

This makes anonymous data much easier to work with, since you don’t have to worry about the principles of consent, legitimate interests, data subject access requests, the right to be forgotten, and a host of other requirements that protect personal data.

The ICO continues:

“You can consider data to be effectively anonymised if people are not (or are no longer) identifiable.”

Sounds simple enough. But unfortunately, anonymisation isn’t a “one and done” process where you hash names and emails, mask sensitive strings, and then clock off early for a few drinks. You have to consider where the data will be going, who else will be using it, and what other data they may have.

As the ICO explains: “identifiability may be viewed as a spectrum that includes the binary outcomes at either end, with a blurred band in between:

- at one end, information relates to directly identified or identifiable people (and will always be personal data); and

- at the other end, it is impossible for the person processing the information to reliably relate information to an identified or identifiable person. This information is anonymous in that person’s hands. “

This means that anonymisation is subject to context: the same exact data could be deemed anonymous in one person’s “hands” and only pseudonymous in another’s.

This point has been borne out in the courts a few times, for example in the case of EDPS v SRB. Here is the very short version of that story:

- SRB Shared Data: The SRB shared pseudonymised data with Deloitte for analysis, which the EDPS initially argued required informed consent.

- Court’s Key Finding: A court ruled that the data was considered fully anonymous in Deloitte’s possession because the firm lacked the means to reidentify individuals.

- Outcome: Based on the finding of anonymity, the court determined the SRB was justified in sharing the data without needing to obtain informed consent or rely on legitimate interests.

This is very helpful because it allows data to be shared with a broader range of organisations whilst maintaining anonymity. But the converse is also true: if shared with an organisation that would be capable of reidentifying that data due to other information they have available, it can cease to be anonymous and become only pseudonymous (and therefore personal).

Anonymisation in practice

There are several techniques used to anonymise data. We’ll explore them in more detail in part 3 but first, let’s define a few key terms to understand what true anonymization looks like in practice:

- Hashing: Transforming data into a fixed-length string using a mathematical algorithm. Hashing is irreversible, so strings cannot be reverse-engineered, though they can be re-created if the original (pre-hash) string and algorithm are known.

- Salting: Adding random data (a “salt”) to a value before hashing it, to make the hash output unique and very difficult to recreate, even if the original (unsalted) value is the same.

- Perturbation: Modifies data slightly to protect privacy while preserving the overall pattern for analysis

For illustration purposes, let’s look at an example involving two fictional companies named Skywalker and Kenobi. Skywalker is a transaction processing software company. Kenobi is a research company.

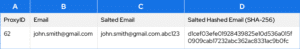

Skywalker provides Kenobi with transaction data to develop insights about consumer habits. Before sharing data, Skywalker hides customer emails by salting and then hashing the email.

Example:

Skywalker only shares the ProxyID and the Salted Hashed Email with Kenobi – but not the original or the salted email.

Why It’s Safe (and Not So Safe)

- Kenobi, the research company, doesn’t know the salt value “.abc123” Skywalker used to create the final hashed email, so they can’t reverse the values to find the real email. To them, the data is anonymous.

- Any Skywalker data engineer with access to the salted email could recreate the salted hash by buying email lists, applying common hashing methods, and matching the result to column D. This process costs little and doesn’t involve hacking or lawbreaking.

- That means the “salted hashed email” is pseudonymous for Skywalker (still considered personal data).

But wait! There’s more. Skywalker transmits more than just a hashed email address to Kenobi; they also share transactions linked to the same set of IDs.

Example:

Transactions

This information is safe to share with Kenobi because they don’t know who “ProxyID 62” belongs to. They only know that “ProxyID 62” went to McDonald’s once. But, just to be safe, some perturbation is added before the data is sent to Kenobi – enough to make reidentification very difficult, but not enough to change the data in a statistically significant way:

Example:

The Problem

Now, let’s say McDonald’s hires the research company, Kenobi, to run an analysis on share of wallet and customer loyalty.

McDonald’s has its own data from its ordering app showing what customers bought:

If Kenobi sends the McDonald’s data team the file containing transactions pertaining to ProxyID 62, McDonald’s could (theoretically) cross-reference that against their CRM and PoS data and notice that one customer (McID 37) matches all the same McDonald’s visits and amounts. From that, McDonald’s could guess that their customer also went to Burger King. This means Kenobi has just told them that McID 37 visited Burger King on 18th August, even though that wasn’t supposed to be known!

Since McDonald’s also holds personal data on McID 37 – such as their name and email address from their app registration – there is a risk that the research company has just disclosed personal data on customer 62. Oops!

Why this matters

- In the US, the research company could require McDonald’s to agree to contractual commitments saying that (among other things) they will store the transaction data on separate systems that don’t contain any personal data whatsoever, with separate access controls, and that they won’t combine the transactions with any other data that could re-identify people. These are all good and sensible protections.

- Under GDPR, the research company would need to go further. That’s because of the “motivated intruder test”, which means that contractual commitments aren’t enough if you’ve handed out enough different pieces of information.

- If a mal intended competent person can reassemble data to re-identify someone or obtain new facts, the data is no longer anonymous under GDPR

We need a way to guarantee the safety of the information with hard technical constraints (stay tuned for part 3!).

Conclusion: Why this matters now more than ever

As the volume and granularity of consumer data continue to grow, so too does the responsibility of those who handle it. With cyber-attacks on the rise and major brands falling victim seemingly every month (M&S, Co-op, Jaguar Land Rover to name a few recent examples in the UK), the need for hard protections and a clear distinction between anonymous data and personal data is increasingly apparent.

The stakes are high: a misstep can erode trust, invite regulatory scrutiny, and compromise the very relationships that businesses rely on.

By embracing advanced privacy-preserving technologies like clean rooms—and applying them thoughtfully and rigorously—companies can unlock the full potential of their data while honoring the trust placed in them by customers.

In short, privacy isn’t a barrier to innovation. It’s the foundation of it.

In part 3 of this blog series, I’ll conclude by explaining how it’s possible to enforce the hard technical constraints needed to ensure privacy and the role that clean rooms play in that.